English physician William Harvey is credited with having been the first doctor to discover the circulation of blood in 1628. The first successful blood transfusion was performed by another physician – Richard Lower – in 1665 when he managed to keep dogs alive by transfusion of blood from other dogs.

The first successful transfusion of human blood was used to treat postpartum haemorrhage (excessive loss of blood following childbirth), this time performed by British obstetrician Dr James Blundell in 1818.

(Earlier, in 1795, American physician Philip Syng Physick had succeeded in performing what would have been recognised as the first successful human blood transfusion. He however failed to publish his results).

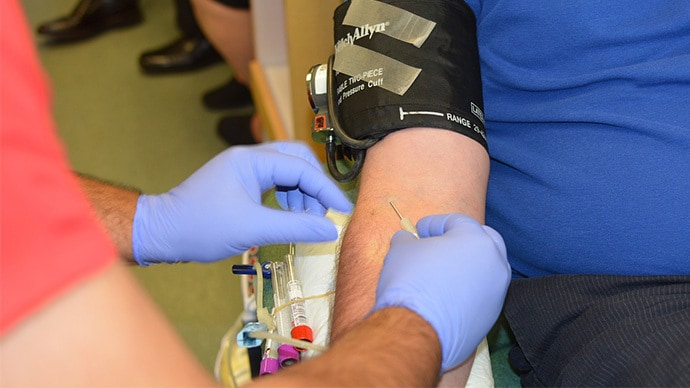

Traditional Blood Transfusions

For two centuries, then, blood transfusion has been a critical life-saving mechanism that has been used on patients who have experienced heavy blood loss through accidents, childbirth, surgery and other ways. While blood transfusion will remain an important part of medical practice, recent scientific development may however relegate the practice of donating blood to no more than a medical curiosity.

Stem cells have in recent years significantly altered the medical landscape. They are literally the building blocks of life. A complete human being develops from a fertilised egg cell, which is the first stem cell. By definition stem cells are undifferentiated cells that can give rise to indefinitely more cells of the same type and, crucially, certain other kinds of cells arise by differentiation. This characteristic of stem cells gives doctors an unlimited supply of cells to work with to heal injuries and cure diseases.

Creating Blood using Stem Cells

Scientists have now shown that it is possible to create blood using stem cells. This project, starting in 1998, has been 20 years in the making, when embryonic stem cells were first isolated. Blood-forming stem cells have now been successfully differentiated with the process centring on reprogramming a patient’s own skin cells. The process involved exposing the stem cells to a chemical soup which prompted them to become a tissue, which in turn makes blood stem cells. The tissue was tested in mice and successfully produced new blood cells. Dr George Daley, a researcher and dean of Harvard Medical School is confident that the work of two decades will soon be crowned with success when the process is replicated in humans and, as he says, generate ‘bona fide human blood stem cells in a dish.’ This process has the potential of making available to doctors an unlimited supply of blood and immune cells for transplants.

The perennial shortage of donated blood would no longer be the hindrance that it is today. Concern has been raised in England, for instance, where blood donation (once a time-honoured tradition) has seen a dramatic decline of 24.4% in 2015, compared to 2005 figures. Drug screening would become a more efficient process and personalised treatments for blood disorders would become the norm.

This new development, with its potential for providing an unlimited supply of blood stem cells, would provide an important backup to traditional blood banks in case of emergencies and would eventually be the default system of replenishing blood.

Persons with genetic blood disorders would benefit greatly from this new process as it would be possible to correct their genetic defects (using gene editing) and make ‘clean’ functional blood cells.

H/T: The Telegraph

English

English