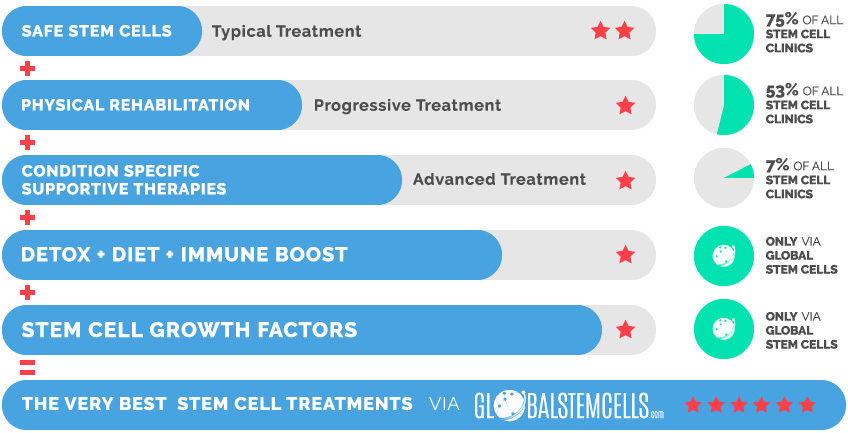

Unique Access provides access to an extensive treatment protocol for Multiple Sclerosis (MS) which utilises higher quantities of stem cells, extensive rehabilitation, and many supportive therapies and supplements. This effective combination of the most advanced medical technologies with functional medicine has helped patients achieve significant improvements.

Why Stem Cells Work For Multiple Sclerosis

Extensive research from multiple research organizations over the last decade has led to the conclusion that stem cell transplantation is the most promising treatment modality not only to improve the condition and prevent secondary complications but also to reverse the neurological damage.

Moreover, stem cells regulate the immune system’s response against the nerve cells and release growth factors which promote cell growth, differentiation, and stimulate the brain’s own stem cells to speed up the recovery process.

Mechanisms

Recent published research showed that Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) treatment is a potential treatment remedy for Multiple Sclerosis patients.

The mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) for Multiple Sclerosis are based on the following aspects:

(1) Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) exert their immunomodulatory functions on numerous immune cells including T cells, B cells, NK cells and dendritic cells (DCs). Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) on one side induced peripheral T cell tolerance to myelin proteins, thus reducing migration of pathogenic T cells to the CNS and, on the other side, homed themselves to the CNS where they preserved axons and reduced demyelination.

(2) Mesenchymal Stem Cells can protect axons and improve neuronal survival, possibly via anti-apoptotic effects, anti-oxidant effects, or the release of trophic factors.

(3) Mesenchymal Stem Cells can induce endogenous neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis.

(4) Mesenchymal Stem Cells can decrease production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

(5) Mesenchymal Stem Cells also appear to reduce gliotic scar formation – gliosis representing a major barrier to spontaneous repair.

Possible Improvements

Most of the Multiple Sclerosis patients Global Stem Cells has helped to receive innovative treatments, with the combination of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC), supportive therapies and rehabilitation, showed visible improvements in motor function, sensation, bowel and bladder control, muscle tone and strength, balance and coordination, vision, memory and cognition.

Moreover, the disease progression has been observed to be significantly slower after the treatment.

Multiple Sclerosis patients treated with stem cells usually observe improvements in the following areas:

- Motor Function

- Sensitivity

- Balance

- Coordination

- Neuropathic Pain

- Fatigue

- Vision

- Tremors

- Bladder & Bowel Control and more

Our Promise

We believe that there is always hope and that patients deserve access to effective and safe treatments.

We are independent with an in-house medical department.

We combine internationally accredited hospitals, next generation treatments, unique products and services that are integrative and effective to ensure best possible treatment results.

Multiple Sclerosis Testimonial

Testimonial Disclaimer: All examples of what has been achieved by others should not be taken as typical or in any way a guarantee or projection of what any individual can expect from treatment.

Chris Negus was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) in New Zealand and had difficulty walking due to his condition. He sought Stem Cell Treatment with Verita Neuro in Bangkok and is very happy with the results of the treatment he received. In this video, Chris and his wife describe his improvements and also share a special message of hope to all others living with Multiple Sclerosis.

Stem cells

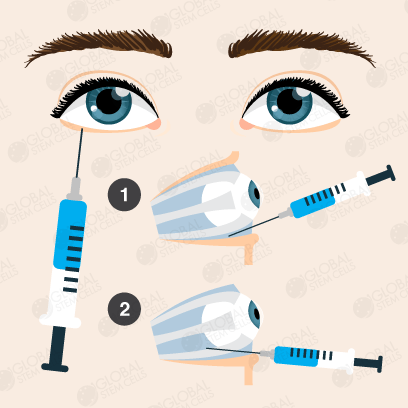

In terms of stem cells we will make sure that the patient will receive the correct and necessary stem cell type, quality, quantity and viability. Our exclusive research partner guarantee a stem cell viability of 95%, many injections have a staggering viability of 98-99%.

Supportive Therapies & Remedies

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Chamber (HBOT)

- Hemo Oxygen Therapy (HOT)

- IV Vitamin Drips

- Immune-Boosting Supplements (e.g. GcMAF)

Partner Hospital

The treatment will take place in an internationally accredited tertiary care hospital and not in a hotel or clinic. This is important for the patient’s safety and care as the patient will have access to all specialized departments & specialist doctors which will further increase the treatments efficiency.

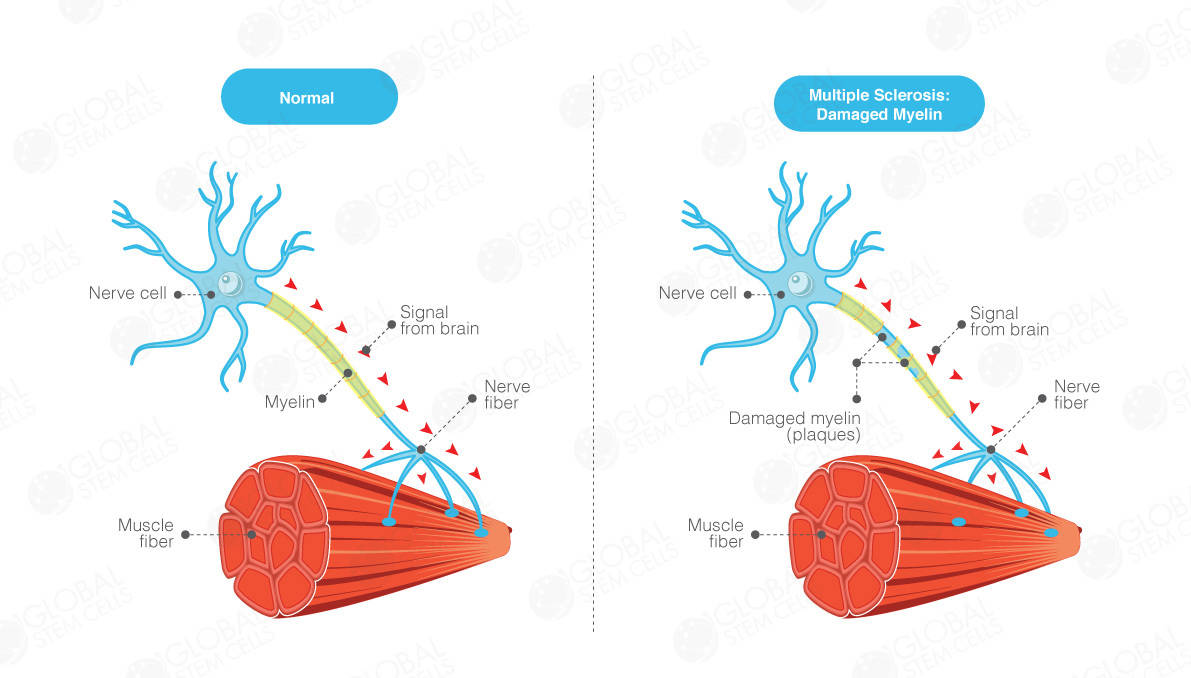

What is Multiple Sclerosis (MS)?

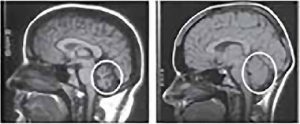

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a common neurological disease and a major cause of disability, particularly affecting young adults. It is characterised by patches of damage occurring throughout the brain and spinal cord, with loss of myelin sheaths – the insulating material around nerve fibers that allows normal conduction of nerve impulses. Multiple Sclerosis (MS) affects over two million people worldwide and shows a clear gender bias, with women being affected twice as frequently as men.

Etiology of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is still unknown; it is generally thought that the disease will develop in genetically susceptible individuals as a result of an autoimmune response directed against components of myelin. An environmental agent or event (virus, bacteria, chemicals, lack of sun exposure) has been hypothesised to act in concert with a specific genetic predisposition to result in immune dysfunction.

Ways in which Multiple Sclerosis affects the body

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) affects principally young adults and leads to severe physical and cognitive impairment. Multiple Sclerosis (MS) follows a relapsing-remitting (RR) course in 85% and a primary progressive (PP) course in 15% of patients. In the majority of RR patients, secondary progression (SP) occurs after a median interval of 19 years, with persisting relapses in 40% of cases.

Overall, Multiple Sclerosis (MS) patients lose the ability to walk independently at a median age of 63 years, but 1-3% of patients suffer from the malignant form of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and reach this level of disability only in a few weeks or months. Multiple Sclerosis (MS) also leads to visual disturbances, loss of sensation, speech and swallowing dysfunction, bowel and bladder incontinence, and erectile dysfunction.

The Very Best Stem Cell Treatments via globalstemcells.com

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. November 19, 2015.

“NINDS Multiple Sclerosis Information Page”. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Compston A, Coles A (October 2008).

Compston A, “Multiple sclerosis”. Lancet. 372 (9648): 1502–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. PMID 11955556.

- Tsang BK, Macdonell R (December 2011).

“Multiple sclerosis- diagnosis, management and prognosis”. Australian family physician. 40 (12): 948–55. PMID 22146321.

- Berer K, Krishnamoorthy G (April 2014).

“Microbial view of central nervous system autoimmunity”. FEBS Letters. S0014-5793 (14): 00293–2. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.007. PMID 24746689.

- Milo R, Kahana E (March 2010).

“Multiple sclerosis: geoepidemiology, genetics and the environment”. Autoimmun Rev. 9 (5): A387–94.

doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.010. PMID 19932200.

- Cohen JA (July 2009).

“Emerging therapies for relapsing multiple sclerosis”. Arch. Neurol. 66 (7): 821–8. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.104. PMID 19597083.

- Marrie RA (December 2004).

“Environmental risk factors in multiple sclerosis aetiology”. Lancet Neurol. 3 (12): 709–18. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00933-0. PMID 15556803.

- Alonso A, Hernán MA (July 2008).

“Temporal trends in the incidence of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review”. Neurology. 71 (2): 129–35.

doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316802.35974.34. PMC 4109189. PMID 18606967.

- Pugliatti M, Sotgiu S, Rosati G (July 2002).

“The worldwide prevalence of multiple sclerosis”. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 104 (3): 182–91.

doi: 10.1016/S0303-8467(02)00036-7. PMID 12127652.

- Edward T. Bope; Rick D. Kellerman (22 December 2011).

Conn’s Current Therapy 2012: Expert Consult – Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 662–. ISBN 1-4557-0738-4.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. November 19, 2015.

“NINDS Multiple Sclerosis Information Page”. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- Compston A, Coles A (October 2008).

Compston A, “Multiple sclerosis”. Lancet. 372 (9648): 1502–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. PMID 11955556.

- Tsang BK, Macdonell R (December 2011).

“Multiple sclerosis- diagnosis, management and prognosis”. Australian family physician. 40 (12): 948–55. PMID 22146321.

- Berer K, Krishnamoorthy G (April 2014).

“Microbial view of central nervous system autoimmunity”. FEBS Letters. S0014-5793 (14): 00293–2. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.007. PMID 24746689.

- Milo R, Kahana E (March 2010).

“Multiple sclerosis: geoepidemiology, genetics and the environment”. Autoimmun Rev. 9 (5): A387–94.

doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.010. PMID 19932200.

- Cohen JA (July 2009).

“Emerging therapies for relapsing multiple sclerosis”. Arch. Neurol. 66 (7): 821–8. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.104. PMID 19597083.

- Marrie RA (December 2004).

“Environmental risk factors in multiple sclerosis aetiology”. Lancet Neurol. 3 (12): 709–18. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00933-0. PMID 15556803.

- Alonso A, Hernán MA (July 2008).

“Temporal trends in the incidence of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review”. Neurology. 71 (2): 129–35.

doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316802.35974.34. PMC 4109189. PMID 18606967.

- Pugliatti M, Sotgiu S, Rosati G (July 2002).

“The worldwide prevalence of multiple sclerosis”. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 104 (3): 182–91.

doi: 10.1016/S0303-8467(02)00036-7. PMID 12127652.

- Edward T. Bope; Rick D. Kellerman (22 December 2011).

Conn’s Current Therapy 2012: Expert Consult – Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 662–. ISBN 1-4557-0738-4.

English

English